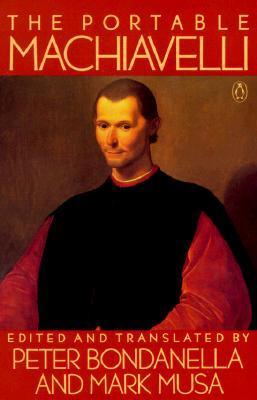

The Portable Machiavelli

by Niccolo Machiavelli (edited and translated by Peter Bondanella and Mark Musa)

Penguin (31 May 1979)

What’s it about?: A collection of personal and professional writings by Florentine diplomat and philosopher Niccolo Machiavelli. It includes complete texts of The Prince, Belfagor, and Castruccio Castracani. An abridged version of The Discourses is also included, along with the play The Mandrake Root, seven private letters, and some extracts from The Art of War and The History of Florence.

My opinion: This is a good volume to have in your collection, whether you’re a casual reader or a lover of all things Machiavelli. His best known work is The Prince, a book that many people — rich and ordinary alike — pretend to have read. I would ask anyone considering exploring Machiavelli’s works to take them slowly, and really take your time. You also have to understand what he means when he talks about making an example of an enemy. This is Florence in the sixteenth-century we’re talking about. There was no calling people out on social media, no internet, no computers. Calling someone out back then meant putting their head on a pike.

To say that Machiavelli is misunderstood would be an understatement. Some deliberately miss the point of his works. Others focus on particular aspects and hypertrophy them. He has become synonymous with deception and scheming, and in recent years, his texts have become increasingly associated with toxic masculinity, pick-up artists and other such fringe movements. Let me ask: Have the works of the Florentine diplomat ever served any of those people? Nothing in them can be considered prescriptive, and anyone claiming he’s laying out a treatise for how a man ought to live is simply wrong. Yes, you have your “This works because…” sentences, but it really only amounts to a collection of observations on how power is attained, maintained, and taken. He is, above all else, a great historian. Not a good historian, but a great one. His interest in human affairs and the recovery of lost knowledge make for some fascinating reading, and he urges others to study history as well.

The Prince shouldn’t be taken as representative of Machiavelli’s views. Many people refuse or forget to acknowledge that it was written for a very narrow and specific audience, i.e. to gain favour with Lorenzo de’ Medici, who had seized control of Florence at the time. That might not have been his only goal verbatim, but the text did serve as a gift and manual of sorts. That he contradicts himself every other sentence should be a pretty strong indicator of the deliberate nature of it all. Other works of his have a commanding tone, but in The Prince, much of his language is ambiguous, contradictory, and often seems deliberately provocative. Was Medici supposed to “get it”? I don’t know.

Then there’s an abridged version of The Discourses. I would recommend the complete text, of course, but the version here makes for a decent crash course into Machiavelli’s beliefs beyond The Prince. I was amazed to find that the phrase “Five Good Emperors” originated in this text, referring to the Roman emperors up to and including Marcus Aurelius. Their succession is based on judgement and merit, rather than by virtue of birth.

Though not a complete collection, the personal letters included in this volume offer some valuable insights. They reveal his intelligence, humour, and ideas on literature, history, politics, and society. In addition to telling the reader about his early life, they show personal context that can really colour Machiavelli’s writing.

This volume is not a definitive collection of Machiavelli’s works, but simply a reader. The Prince is complete, but The Discourses and other works are heavily abridged and the footnotes come in handy for any reader looking to dispel some of the myths surrounding the author. All of which is totally appropriate for a text titled The Portable Machiavelli.

Again, I advise reading these works slowly, footnotes included. The Portable Machiavelli is an excellent volume, for those looking for a solid introduction to the Florentine diplomat, or for anyone interested in history and philosophy.