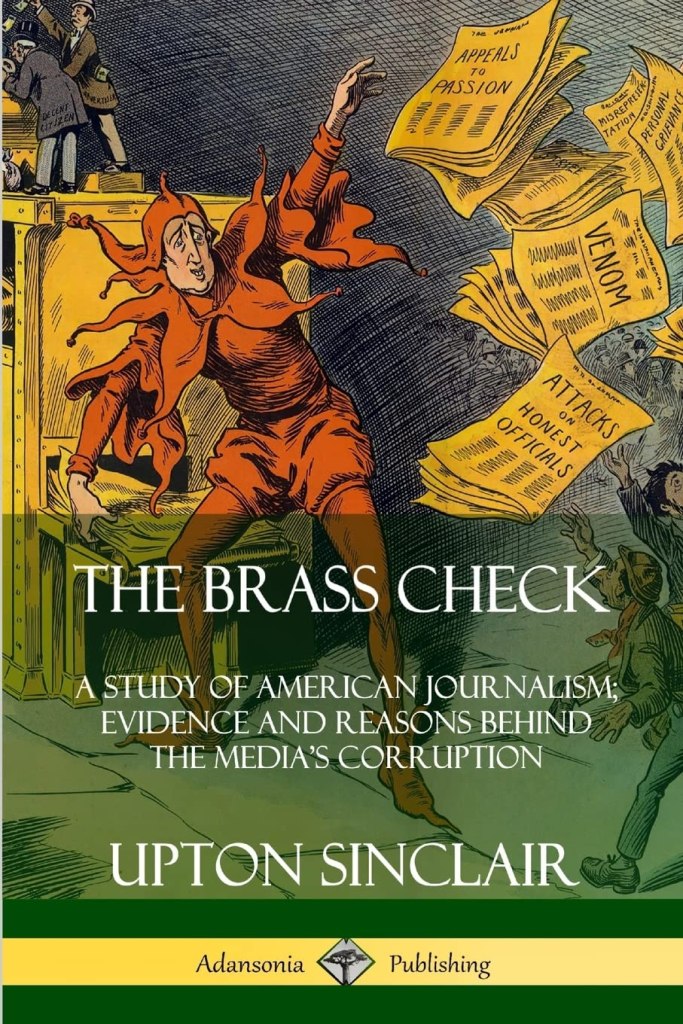

The Brass Check is Upton Sinclair’s account of journalism as an industry, published in 1919. The term “brass check” refers to money given secretly to journalists for their service, as a sort of pay-for-play racket of the media ecosystem in the early twentieth century. This lays the groundwork for the text. To quote Sinclair, “It is the thesis of this book that American newspaper as a whole represent private interests and not public interests.”

Sinclair called The Brass Check “the most important and dangerous book I have ever written.” Most newspapers refused to review the text, and Sinclair challenged the press to refute any inaccuracies in it. A lot of what he discusses is anecdotal, and he was something of a muckraker himself, but he clearly understood the economic incentives of journalism back then.

Readers may be more familiar with The Jungle, a novel where Sinclair portrays the living and working conditions of those who worked in the Chicago stockyards, and government and business corruption. In The Brass Check, he fixes his gaze on tabloid journalism as a racket. Rumours, gossip, and outright lies, in an effort to drive up profits and destroy the reputations of business rivals. Newspapers in the early twentieth century would destroy the reputations of socialists, progressives, or anyone looking to improve the lot of the working class. Fact checking? Why even bother?

Sinclair ran into a lot of trouble trying to get his works to print. Demands for revision and whathaveyou. Not only was The Brass Check self-published, but he didn’t even copyright it. Part of this was likely the hope of bypassing the gatekeepers. Part of it was also a desire to make his knowledge more freely available, regardless of whatever strictures were in place. As such, it is freely available on the internet.

Sinclair’s understanding of the media ecosystem, and the pressures and incentives that went with it, were thorough. He knew how these structures and dynamics would impact the writer’s and people’s understanding of events. Those incentives and pressures are very much alive today, with news blogs and social media being well and truly established. Different, but the same. You might no longer have those paper boys standing on the street corners, shouting “Extra, extra, read all about it!” In its place is the wonderful world of page views and page view bonuses, and the need to cram the story into the headline.

One can’t help but compare The Brass Check and Ryan Holiday’s 2012 debut, Trust Me, I’m Lying. Published almost a century apart, but the similarities are many. It makes me wonder how much time people spent reading the tabloids then compared to now.

Then there’s the constant back-and-forth. Given how today’s powerful figures are quick to cry “Fake news!” in the face of any sort of media criticism, then it’s kind of fitting to revisit Sinclair’s text and the history of these kinds of public showcases.

Then you start to think that nothing has changed, and you can only ask yourself what can be done.

For all the things that have changed, or stayed the same, it makes The Brass Check more relevant than ever to me, and that’s why I find it such a fascinating read.