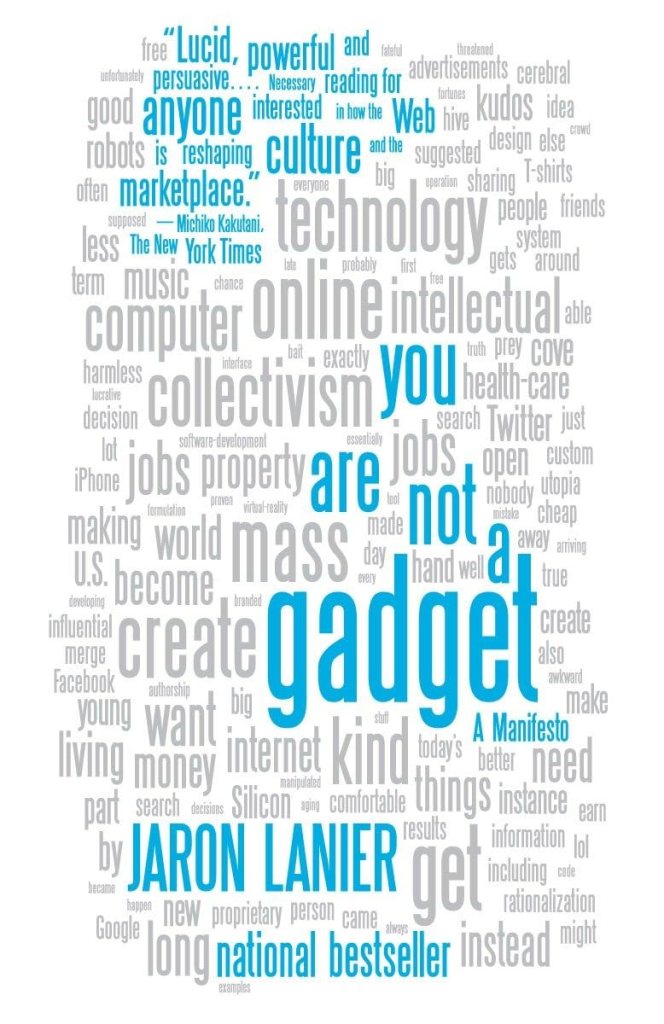

First published in 2010, You Are Not a Gadget is not only one of the best books on media in existence, but also one of my favourite books in general. Like, if I ever had a top one-hundred, this would definitely sit comfortably on such a list. In the text, computer scientist and visual artist Jaron Lanier critiques the dominant philosophies behind digital culture, especially those he sees as reducing individuals to mere components of larger information networks. What he proposes is a more human-centred approach to technology and innovation, and he does so without forcing his conclusions onto you.

Core themes include his critique of collectivism and “Digital Maoism;” lock-in and design constraints; digital reductionism; anti-technological utopianism; and his call for individual creativity. He criticises these aspects of the web in a way that’s not only him making crucial observations, but inviting the reader to think about them as well.

Lanier criticises the belief that crowd-sourced platforms — like Wikipedia or any open-source movement — necessarily produces better outcomes. He warns that the “wisdom of crowds” can lead to mob behaviour or just general mediocrity. I tend to agree. “Wisdom of crowds”? No. Crowds are dumb. Do you listen to top forty radio? No? Well, the crowds out here have decided that it’s great music that everyone needs to hear blasting from their speakerphones on public transport. I wouldn’t put too much stock in what the masses think.

Then there’s his argument that anonymity can de-individuate, and erode accountability, creativity, and authenticity.

“If you win anonymously no one knows,” he says. “And if you lose, you just change your pseudonym and start over, without having modified your point of view one bit. If the Troll is anonymous and the target is known then the dynamic is even worse.” I can see his point, but I like to think there’s more to anonymity than just trolling and shitposting. Sometimes, I like the idea of how forums used to be, where one could have their username and avatar, and shoot the breeze. People weren’t personal brands, they just were. This isn’t so much a counterargument as much as it is a bit of mild pushback. I completely agree that things get toxic when anonymity is used for trolling and harassment.

In terms of lock-in and design constraints, Lanier discusses how early technological decisions like file formats or UI models become “locked in,” stifling innovation. He criticises MIDI for its flattening of musical expression. He also believes social media platforms enforce rigid identity structures, discouraging nuance and the evolution of the self.

When I was first introduced to it, I found Facebook had this very problem of lock-in constraints. The blue-and-white colour scheme was way too sterile and office-like for my tastes, and I resented how the timeline and “about” sections of people’s profiles reduced everyone to video game-like stats, essentially. Reducing the individual to fit a social networking template seems a bit insane. It’s one reason I deactivated and subsequently deleted my account many years ago. Of course, I came back a few years later, at the suggestion of a professor who believed it to be a means of networking and staying in touch with colleagues. And it has been positive in that sense, but I still see Lanier’s point. I’m just glad it’s not as bad as LinkedIn.

One of Lanier’s issues that is perhaps more relevant than ever is that of digital reductionism. He warns against reducing humans to data points, algorithms, or profiles. He argues that human consciousness and individuality are far too complex to be capture by code, and that treating people like gadgets shows a lack of empathy, depth, and subjective experience.

He then takes aim at the utopianism of Silicon Valley types, especially ideologies like technological determinism (the idea that tech drives progress), singularitarianism (a sort of post-human belief in the merging of human and machine consciousness), and cybernetic totalism (the notion that everything reality and human experience can be captured by computation).

What does Lanier propose then? Throughout the text, he calls for the preservation of personal expression, original authorship, and subjective depth. And, to resist trends that promote the flattening of individual identity, like algorithmic feeds, avatars, remix culture, and the like.

Some might call this elitist. In fact, I think Gawker did at some stage, calling him a “luddite” or something along those lines. Whatever, I’m not going to look it up. I found You Are Not a Gadget to be one of the most original and thoughtful texts on how we figure technology in our lives. The manifesto style is perfect for a subject like this — bold, opinionated, and polemical. Lanier’s blend of personal anecdote, philosophy, computer science, and cultural criticism is particularly engaging. I find I invoke its talking points quite a bit every time the topic of contemporary social media comes up, because so much of it is fertile ground for any discussion on social media and its darker aspects, and how digital systems are shaping human behaviour and society.

That, and it’s a prescient text, anticipating many of the themes that are central in tech criticism today. Think of the documentary The Social Dilemma, Shoshana Zuboff’s book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Patrick Scolyer-Gray’s Artistic Works of Fiction and Falsehood, or the many internal reckonings within the tech industry itself.

You Are Not a Gadget is essential reading for our time, and its importance in our social and technological climate cannot be understated. Highly recommended for fans and sceptics of Web 2.0 alike.